Baltimore

| City of Baltimore | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Independent City — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Charm City,[1] Mobtown,[2] B'more,[3] The City of Firsts,[4] Monument City,[5] Ravenstown[6] |

|||

| Motto: "The Greatest City in America",[1] "Get in on it."[1] "The city that reads."[7] |

|||

|

|||

City of Baltimore

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| Founded | 1729 | ||

| Incorporation | 1797 | ||

| Named for | Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore | ||

| Government | |||

| - Type | Independent City | ||

| - Mayor | Stephanie C. Rawlings-Blake (D) | ||

| - Baltimore City Council |

Council members

|

||

| - Houses of Delegates |

Delegates

|

||

| - State Senate |

State senators

|

||

| - U.S. House |

Representatives

|

||

| Area | |||

| - Independent City | 92.07 sq mi (238.5 km2) | ||

| - Land | 80.8 sq mi (209.3 km2) | ||

| - Water | 11.27 sq mi (29.2 km2) 12.2% | ||

| - Urban | 3,104.46 sq mi (8,040.5 km2) | ||

| Elevation[8] | 33 ft (10 m) | ||

| Population (2009)[9][10] | |||

| - Independent City | 637,418 (20th) | ||

| - Density | 7,889.3/sq mi (3,045.7/km2) | ||

| - Metro | 2,690,886 (20th) | ||

| - Demonym | Baltimorean | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP Code | 21201–21231, 21233–21237, 21239–21241, 21244, 21250–21252, 21263–21265, 21268, 21270, 21273–21275, 21278–21290, 21297–21298 | ||

| FIPS code | 24-04000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0597040 | ||

| Website | www.baltimorecity.gov | ||

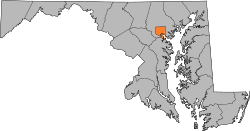

Baltimore (pronounced /ˈbɒltɨmɔr/) is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the U.S. state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River,[11] an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore City in order to distinguish it from surrounding Baltimore County. Founded in 1729, Baltimore is a major U.S. seaport and is situated closer to major Midwestern markets than any other major seaport on the East Coast. Baltimore's Inner Harbor was once the second leading port of entry for immigrants to the United States and a major manufacturing center. The harbor is now home to Harborplace, a shopping, entertainment, and tourist center, and the National Aquarium in Baltimore. After a decline in manufacturing, Baltimore shifted to a service-oriented economy. Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Hospital are now the city's largest employers.

As of 2009, the population of Baltimore was 637,418.[10] The Baltimore Metropolitan Area has approximately 2.7 million residents; the 21st largest in the country. Baltimore is also the largest city in the surrounding associated combined statistical area of approximately 8.4 million residents.[12]

The city is named after Lord Baltimore in the Irish House of Lords, the founding proprietor of the Maryland Colony. Baltimore himself took his title from a place in Bornacoola parish, County Leitrim and County Longford, Ireland.[13] Baltimore is an anglicized form of the Irish Baile an Tí Mhóir, meaning "Town of the Big House",[14] not to be confused with Baltimore, County Cork, the Irish name of which is Dún na Séad.[15]

Contents |

History

The Maryland colonial General Assembly created the Port of Baltimore at Locust Point in 1706 for the tobacco trade. The Town of Baltimore was founded on July 30, 1729, and is named after Lord Baltimore (Cecilius Calvert), who was the first Proprietary Governor of the Province of Maryland. Cecilius Calvert was a son of George Calvert, who became the First Lord Baltimore of County Cork, Ireland in 1625.[16] Baltimore grew swiftly in the 18th century as a granary for sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean. The profit from sugar encouraged the cultivation of cane and the importation of food.

Baltimore played a key part in events leading to and including the American Revolution. City leaders such as Jonathan Plowman Jr. moved the city to join the resistance to British taxes and merchants signed agreements to not trade with Britain. Congress met in the Henry Fite House from December 1776 to February 1777, effectively making the city the capital of the United States during this period. After the war, the Town of Baltimore, nearby Jonestown, and an area known as Fells Point were incorporated as the City of Baltimore in 1797. The city remained a part of Baltimore County until 1851 when it was made an independent city.[17]

The city was the site of the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. After burning Washington, D.C., the British attacked Baltimore on the night of September 13, 1814. United States forces from Fort McHenry successfully defended the city's harbor from the British. Francis Scott Key, a Maryland lawyer, was aboard a British ship where he had been negotiating for the release of an American prisoner, Dr. William Beanes. Key witnessed the bombardment from this ship and later wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner", a poem recounting the attack. Key's poem was set to a 1780 tune by British composer John Stafford Smith, and the Star-Spangled Banner became the official National Anthem of the United States in 1931.

Following the Battle of Baltimore, the city's population grew rapidly. The construction of the Federally-funded National Road (presently U.S. Route 40) and the private Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) made Baltimore a major shipping and manufacturing center by linking the city with major markets in the Midwest. A distinctive local culture started to take shape, and a unique skyline peppered with churches and monuments developed. Baltimore acquired its moniker, "The Monumental City" after an 1827 visit to Baltimore by President John Quincy Adams. At an evening function Adams gave the following toast: "Baltimore: the Monumental City- May the days of her safety be as prosperous and happy, as the days of her dangers have been trying and triumphant."[19] Baltimore suffered one of the worst riots of the antebellum south in 1835, when bad investments led to Baltimore Anti-bank riot.[20]

Maryland did not secede from the Union during the American Civil War; however, when Union soldiers marched through the city at the start of the war, Confederate sympathizers attacked the troops, which led to the Baltimore riot of 1861. Four soldiers and 12 civilians were killed during the riot, which caused Union troops to occupy Baltimore. Maryland came under direct federal administration—in part, to prevent the state from seceding—until the end of the war in April 1865.

Following an economic depression known as the Panic of 1873, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad company attempted to lower its workers wages, leading to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. On July 20, 1877, Maryland Governor John Lee Carroll called up the 5th and 6th Regiments of the National Guard to end the strikes, which had disrupted train service at Cumberland in western Maryland. Citizens sympathetic to the railroad workers attacked the national guard troops as they marched from their armories in Baltimore to Camden Station. Soldiers from the 6th Regiment fired on the crowd, killing 10 and wounding 25. Rioters then damaged B&O trains and burned portions of the rail station. Order was restored in the city on July 21–22 when federal troops arrived to protect railroad property and end the strike.[21]

On February 7, 1904, the Great Baltimore Fire destroyed over 1,500 buildings in 30 hours and forced most of the city to rebuild. Two years later, on September 10, 1906, the Baltimore American newspaper reported that the city had risen from the ashes and "one of the great disasters of modern time had been converted into a blessing." The city grew in area by annexing new suburbs from the surrounding counties, the last being in 1918. A state constitutional amendment approved in 1948, required a special vote of the citizens in any proposed annexation area, effectively preventing any future expansion of the city's boundaries.[22]

The city's population rose from 23.8% black in 1950 to 46.4% in 1970.[23] The Baltimore riot of 1968 occurred following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968. Coinciding with riots in other cities, public order was not restored until April 12, 1968. The Baltimore riot cost the city of Baltimore an estimated $10 million (US$ 63 million in 2011) . Maryland National Guard troops and 1,900 federal troops were ordered into the city. Lasting effects of the riot can be seen on the streets of North Avenue, Howard Street, and Pennsylvania Avenue where long stretches of the streets remain barren.[24]

During the 1970s, Baltimore's downtown area known as the Inner Harbor, had been neglected and was only occupied by a collection of abandoned warehouses. Efforts to redevelop the downtown area started with the construction of the Baltimore Convention Center, which opened 1979. Harborplace, an urban retail and restaurant complex opened on the waterfront in 1980, followed by the National Aquarium in Baltimore, Maryland's largest tourist destination, and the Baltimore Museum of Industry in 1981. In 1992, the Baltimore Orioles baseball team moved from Memorial Stadium to Oriole Park at Camden Yards, located downtown near the harbor. Six years later the Baltimore Ravens football team moved into M&T Bank Stadium next to Camden Yards.[25]

On January 17, 2007, Sheila Dixon became the first female Mayor of Baltimore.[26] On December 1, 2009 she was convicted of fraud and subsequently resigned.

The city has a number of properties on the National Register of Historic Places.[27]

Geography

Baltimore is in north-central Maryland on the Patapsco River close to where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. The city is also located on the fall line between the Piedmont Plateau and the Atlantic Coastal Plain, which divides Baltimore into "lower city" and "upper city". The city's elevation ranges from sea level at the harbor to 480 feet (150 m) in the northwest corner near Pimlico.[28]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 92.1 square miles (239 km2), of which, 80.8 square miles (209 km2) of it is land and 11.3 square miles (29 km2) of it is water. The total area is 12.24 percent water.

Climate

Baltimore lies within the humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa), according to the Köppen classification.

July is typically the hottest month of the year, with an average temperature of 80.4 °F (26.9 °C). Summer is also a season of high (generally, not consistently) humidity in the Baltimore area. The record high for Baltimore is 107 °F (42 °C), set in 1936.[29] January is the coldest month, with an average temperature of 34.9 °F (1.6 °C). However, winter warm fronts can bring periods of springlike weather, and Arctic fronts can drop nighttime low temperatures into the teens. The record low temperature for Baltimore is −7 °F (−21.7 °C), set in 1934.[29] Due to an urban heat island effect in the city proper and a moderating effect of the Chesapeake Bay, the outlying and inland parts of the Baltimore metro area are usually cooler than the city proper and the coastal towns.

As is typical in most East Coast cities, precipitation is generous and very evenly spread throughout the year. Every month typically brings 3–4 inches of precipitation, averaging around 43 inches (1,100 mm) annually. Spring, summer and fall bring frequent showers and thunderstorms, with an average of 105 sunny days a year. Winter often brings lighter rain showers of longer duration, and generally less sunshine and more clouds. Snowfall occurs occasionally in the winter, with an average annual snowfall of 18.8 inches (48 cm),[30] In the northern and western suburbs, annual temperatures are cooler, and winter snowfall is more significant, and some areas average more than 20 inches (51 cm) of snow.[31] Freezing rain and sleet occurs a few times each winter in Baltimore, as warm air over rides cold air at the upper levels of the atmosphere. The cold air gets trapped against the mountains to the west and the result is freezing rain or sleet.

The average date of first freeze in Baltimore is November 13, and the average last freeze is April 2.[32]

NOTE: The temperature data presented below was recorded at Inner Harbor; all other data recorded at BWI Airport.

| Climate data for Baltimore (Inner Harbor) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.7 (5.39) |

44.7 (7.06) |

54.9 (12.72) |

65.5 (18.61) |

75.7 (24.28) |

84.6 (29.22) |

88.7 (31.5) |

86.8 (30.44) |

79.9 (26.61) |

68.4 (20.22) |

57.2 (14) |

46.1 (7.83) |

66.2 (19) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 28.0 (-2.22) |

29.9 (-1.17) |

38.2 (3.44) |

47.5 (8.61) |

57.8 (14.33) |

67.3 (19.61) |

72.0 (22.22) |

70.5 (21.39) |

63.3 (17.39) |

51.4 (10.78) |

42.1 (5.61) |

32.5 (0.28) |

50.0 (10) |

| Precipitation inches (mm) | 3.47 (88.1) |

3.02 (76.7) |

3.93 (99.8) |

3.00 (76.2) |

3.89 (98.8) |

3.43 (87.1) |

3.85 (97.8) |

3.74 (95) |

3.98 (101.1) |

3.16 (80.3) |

3.12 (79.2) |

3.35 (85.1) |

41.94 (1,065.3) |

| Snowfall inches (cm) | 7.0 (17.8) |

6.4 (16.3) |

2.4 (6.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

1.7 (4.3) |

18.1 (46) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 116.5 |

| Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 9.7 |

| Sunshine hours | 155.0 | 166.7 | 213.9 | 231.0 | 254.2 | 276.0 | 291.4 | 263.5 | 222.0 | 204.6 | 159.0 | 145.7 | 2,583 |

| Source: Weatherbase [33], NOAA [34], HKO [35] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

Baltimore exhibits examples from each period of architecture over more than two centuries, and work from many famous architects such as Benjamin Latrobe, George A. Frederick, John Russell Pope, Mies Van Der Rohe and I. M. Pei.

The city has architecturally important buildings in a variety of styles. The Baltimore Basilica (1806–1821) is a neoclassical design by Benjamin Latrobe, and also the oldest Catholic Cathedral in the United States. In 1813 Robert Cary Long, Sr. built for Rembrandt Peale the first substantial structure in the United States designed expressly as a museum. Restored, it is now the Municipal Museum of Baltimore, or popularly the “Peale Museum”. The McKim Free School founded and endowed by John McKim, although the building was erected by his son Isaac in 1822 after a design by William Howard and William Small. It reflects the popular interest in Greece when the nation was securing its independence, as well as a scholarly interest in recently published drawings of Athenian antiquities.

The Phoenix Shot Tower (1828), at 234.25 feet (71.40 m) tall, was the tallest building in the United States until the time of the Civil war. It was constructed without the use of exterior scaffolding. The Sun Iron Building designed by R.C. Hatfield in 1851, was city’s first iron-front building and it was a model for a whole generation of downtown buildings. Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, built in 1870 in memory of financier George Brown, has stained glass windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany and has been called "one of the most significant buildings in this city, a treasure of art and architecture" by Baltimore Magazine.[36][37] The 1845 Greek Revival style Lloyd Street Synagogue is one of the Oldest synagogues in the United States. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, designed by Lt. Col. John S. Billings in 1876 was a considerable achievement for its day in functional arrangement and fire proofing.

I.M.Pei's World Trade Center (1977) is the tallest equilateral pentagonal building in the world at 405 feet (123.4 m) tall.

Future contributions to Baltimore's skyline include plans for a 717 foot (218.5 m) tall structure known as "10 Inner Harbor". The building was recently approved by Baltimore's design panel, but as of January 10, 2010, ARC Wheeler had yet to break ground on the project. It will include luxury condominiums, a hotel, restaurants, and shopping centers. The Naing Corporation has approved a tower of 50–60 floors for the lot at 300 Pratt street, with the design currently being finalized. The Inner Harbor East area will see the addition of two new towers which have started construction: a 24-floor tower that will be the new world headquarters of Legg Mason, and a 21 floor Four Seasons Hotel complex.

The streets of Baltimore are organized in a grid pattern. The streets are lined with tens of thousands of brick and Formstone faced rowhouses. Many consider the rowhouse the architectural form most closely associated to the city. Some rowhouses are dated as far back as the 1790s.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards is considered by many to be the most beautiful baseball park in Major League Baseball, and has inspired many other cities to build their own versions of this Retro-Style Ballpark.

Camden Yards along with the National Aquarium have helped revive the Inner Harbor from what once was an industrial district full of dilapidated warehouses, into a bustling commercial district full of bars, restaurants and retail establishments.

Tallest buildings

| Rank | Building | Height | Floors | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Legg Mason Building | 529 feet (161 m) | 40 | 1973 | [38] |

| 2 | Bank of America Building | 509 feet (155 m) | 37 | 1924 | [39] |

| 3 | William Donald Schaefer Building | 493 feet (150 m) | 37 | 1992 | [40] |

| 4 | Commerce Place | 454 feet (138 m) | 31 | 1992 | [41] |

| 5 | 100 East Pratt Street | 418 feet (127 m) | 28 | 1992 | [42] |

| 6 | Baltimore World Trade Center | 405 feet (123 m) | 32 | 1977 | [43] |

| 7 | Tremont Plaza Hotel | 395 feet (120 m) | 37 | 1967 | [44] |

| 8 | Charles Towers South Apartments | 385 feet (117 m) | 30 | 1969 | [45] |

| 9 | Blaustein Building | 360 feet (110 m) | 30 | 1962 | [46] |

| 10 | 250 West Pratt Street | 360 feet (110 m) | 24 | 1986 | [47] |

Neighborhoods

Baltimore is divided officially into nine geographical regions: Northern, Northwestern, Northeastern, Western, Central, Eastern, Southern, Southwestern, and Southeastern, with each patrolled by a respective Baltimore Police Department district. However, it is common for locals to divide the city simply by East or West Baltimore, using Charles Street as a dividing line, and/or into North and South using Baltimore Street as a dividing line.

The Central region of the city includes the Downtown area which is the location of Baltimore's main commercial area. Home to Harborplace, The Camden Yards Sports Complex (Oriole Park at Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium), the Convention Center, and the National Aquarium in Baltimore, the area also includes many nightclubs, bars and restaurants, shopping centers and various other attractions. It is also the home to many of Baltimore's key business such as Legg Mason and Constellation Energy. In addition, the University of Maryland, Baltimore campus is housed in this area, with the long-associated University of Maryland Medical System adjacent to the school. The downtown core has mainly served as a commercial district with limited residential opportunities. However, since 2002 the population in the downtown has doubled to 10,000 residents with a projection of 7,400 additional housing units coming available by 2012.[48] The Central region also includes the areas north of the downtown core stretching up to the edge of Druid Hill Park. Included in the more northern part of the Central region are the neighborhoods of Mount Vernon, Charles North, Reservoir Hill, Bolton Hill, Madison Park, Druid Heights, as well as several other neighborhoods. These neighborhoods include many residential options and are home to many of the city's cultural opportunities. Maryland Institute College of Art, the Peabody Institute of music, the Lyric Opera House, The Walters Art Museum, The Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, as well as several galleries are all located in this region. Crime in the Inner Harbor and Mount Vernon neighborhoods of the Central District became of greater concern in 2009, as an increasing number of random assaults on tourists were reported.[49][50]

The Northern region of the city lies directly north of the Central region and is bounded on the East by The Alameda and on the West by Pimlico Road. It is a suburban residential area, home to many of the city's upper class residents in neighborhoods including Roland Park, Homeland, Guilford, and Cedarcroft. The Northern region is home to many of Baltimore's notable universities such as Loyola University Maryland, The Johns Hopkins University and College of Notre Dame of Maryland.

The Southern region of the city, a mixed industrial and residential area, consists of the area of the city below the Inner Harbor east of the B&O railroad tracks. It is a mixed socio-economic region consisting of working class ethnically mixed neighborhoods such as Locust Point; the recently gentrified Federal Hill area, home to many working professionals, pubs and restaurants; and low-income residential areas such as Cherry Hill.

The Eastern part of the city consists of the Northeastern, Eastern, and Southeastern regions of the city. Northeastern Baltimore is primarily a residential neighborhood home to Morgan State University bounded by the city line on its Northern and Eastern boundaries, Sinclair Lane, Erdman Avenue, and Pulaski Highway on its southern boundaries and The Alameda on its western boundaries. It has undergone demographic shifts over many years and remains a diverse but predominantly African American region of the city.[51][52][53]

The Eastern region is the heart of what is considered "East Baltimore" and is home to Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Located below Erdman Avenue and Sinclair Lane above Orleans Street, it is almost an exclusively African American area home to low-income residential neighborhoods, several of which constitute many of Baltimore's high crime areas.

The Southeastern region of the city is located below Orleans Street bordering the Inner Harbor on its western boundary, the city line on its eastern boundaries and the Baltimore harbor on its southern boundaries is a mixed industrial and residential area. Home to many young professionals and working class people, it is an ethnically rich section of Baltimore home to many Polish Americans, Greek Americans, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Italian Americans. Upper Fells Point is the center of the city's steadily growing Latino population.

The Western part of the city consists of the Northwestern, Western, and Southwestern regions of Baltimore. The Northwestern region of the city bounded by the county line on its northern and western boundaries, Gwynns Falls Parkway on the south and Pimlico Road on the East is a predominantly residential area home to Pimlico Race Course, Sinai Hospital and several of Baltimore's Synagogues. Once the center of Baltimore's Jewish community, it has undergone white flight since the 1960s and has become an almost exclusively African American area. It is home to many suburban residential areas primarily located above Northern Parkway and several lower-income areas below Northern parkway.

The Western region of the city located west of downtown is the heart of "West Baltimore" bounded by Gwynns Falls Parkway, Fremont Avenue, and Baltimore Street. Home to Coppin State University and Pennsylvania Avenue, it has been the center of Baltimore's African American culture for years and home to many of the city's historical African American neighborhoods and landmarks. Once home to many middle to upper class African Americans, over the years, the more affluent African American residents have since left migrating to other sections of the city in addition to areas such as Randallstown and Owings Mills in Baltimore County and Columbia in Howard County. The area now constitutes a deprived socio-economic group of African American residents and like "East Baltimore", it is known for its high crime rates. Television series, such as The Wire, that concern themselves with Baltimore's crime problems have been based on events that took place in West Baltimore.

The Southwestern region of the city is bounded by Baltimore County to the west, Baltimore Street to the north, and downtown and the B&O railroad to the east. A mixed industrial and residential area, it has gradually shifted from having a predominantly White to a predominantly African American majority.

Belair-Edison |

Homeland |

Woodberry |

Stonewood |

Charles Village |

Carrollton Ridge |

Station North |

Fells Point |

Adjacent communities

The City of Baltimore is bordered by the following communities, all unincorporated census-designated places. All are in adjacent Baltimore County, except Brooklyn Park and Glen Burnie, which are in adjacent Anne Arundel County. In addition, the southern part of the city is bordered by another unincorporated part of northeastern Anne Arundel County.

- Arbutus

- Brooklyn Park

- Catonsville

- Dundalk

- Glen Burnie

- Lansdowne-Baltimore Highlands

- Lochearn

- Overlea

- Parkville

- Pikesville

- Rosedale

- Towson

- Woodlawn

Culture

Historically a working-class port town, Baltimore has sometimes been dubbed a "city of neighborhoods," with over 300 identified districts[54] traditionally occupied by distinct ethnic groups. Most notable today are three downtown areas along the port: the Inner Harbor, frequented by tourists due to its hotels, shops, and museums; Fells Point, once a favorite entertainment spot for sailors but now refurbished and gentrified (and featured in the movie Sleepless in Seattle); and Little Italy, located between the other two, where Baltimore's Italian-American community is based – and where current U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi grew up. Further inland, Mt. Vernon is the traditional center of cultural and artistic life of the city; it is home to a distinctive Washington Monument, set atop a hill in a 19th century urban square, that predates the more well-known monument in Washington, D.C. by several decades.

The traditional local accent has long been noted and celebrated as "Baltimorese" or "Bawlmorese." One thing outsiders quickly notice is that the locals refer to their city as "Bawlamer," dropping with the "t" for the most part. The dialect is similar to that of many Marylanders and Pennsylvanians; it may reflect the region's roots in Cornwall and the English West Country, as many of the original settlers of the Chesapeake Bay area came from this area in colonial times (Traditionally, many Marylanders call their state "Merlin"--and likewise, many Pennsylvanians call their state "Pennsavania," dropping the "l"). However, Baltimore's local accent also reflects the rich mix of ethnic groups from Ireland, Germany, and southern and eastern Europe who immigrated to the city during the industrial era. More recently, references like "B-More" have become common. Baltimore has typically been pronounced "Baldimore" by its residents, changing only the hard "T" sound to a softer, "D" sound. "Bawlamer" pronunciations are used by a subgroup of individuals, most of them now living outside of Baltimore, in surrounding areas like Dundalk and Essex. Newer residents of Baltimore have found ways to profit from the quaintness of the "Bawlamerese" business, and it has become a widespread misunderstanding.

As Baltimore's demographics have changed since World War Two, its cultural flavor and accents have evolved as well. Today, after decades of out-migration to suburbs beyond its corporate limits and significant in-migration of black Americans from Georgia and the Carolinas, Baltimore has become a majority black city with a significantly changed, but still regionally distinctive, dialect and culture. Recently, neighborhoods such as Federal Hill and Canton have undergone extensive gentrification and have proven to be popular places for young professionals and college students to reside. In addition, Latinos are making their mark, notably in Upper Fells Point.

Much of Baltimore's black American culture has roots that long predate the 20th century "Great Migration" from the Deep South. Like Atlanta, Georgia and Washington, D.C., Baltimore has been home to a successful black middle class and professional community for centuries. Before the Civil War, Baltimore had one of the largest concentrations of free black Americans among American cities. In the twentieth century, Baltimore-born Thurgood Marshall became the first black American justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Baltimore's culture has been famously celebrated in the films of Barry Levinson, who grew up in the city's Jewish neighborhoods. His movies Diner, Tin Men, Avalon, and Liberty Heights are inspired to varying degrees by his life in the city.

Baltimore native John Waters parodies the city extensively in his films, including the 1972 cult classic Pink Flamingos. His film Hairspray and its Broadway musical remake are also set in Baltimore.

Each year the Artscape (festival) takes place in the city in the Bolton Hill neighborhood, due to its proximity to Maryland Institute College of Art. It is known as the 'largest free arts festival in America'.

See List of films shot in Baltimore

Performing arts

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is an internationally-renowned orchestra, founded in 1916 as a publicly-funded municipal organization. The current Music Director is Marin Alsop, a protégé of Leonard Bernstein. Center Stage is the premier theater company in the city and a regionally well-respected group. The Baltimore Opera was an important regional opera company, though it filed for bankruptcy in 2008 and is not currently performing.[55] The Baltimore Consort has been a leading early music ensemble for over twenty-five years. The France-Merrick Performing Arts Center, home of the restored Thomas W. Lamb-designed Hippodrome Theatre, has afforded Baltimore the opportunity to become a major regional player in the area of touring Broadway and other performing arts presentations.

Baltimore also boasts a wide array of professional (non-touring) and community theater groups. Aside from Center Stage, resident troupes in the city include Everyman Theatre, Single Carrot Theatre, and Baltimore Theatre Festival. Community theaters in the city include Fells Point Community Theatre and the Arena Players Inc., which is the nation's oldest continuously operating African American community theater.[56]

Baltimore is home to the Pride of Baltimore Chorus, a 3-time International silver medalist women's chorus, affiliated with Sweet Adelines International.

Notable persons

- See List of people from Baltimore

Economy

Once a major industrial town, with an economic base focused on steel processing, shipping, auto manufacturing, and transportation, the city suffered a deindustrialization which cost residents tens of thousands of low-skill, high-wage jobs. While it retains some industry, Baltimore now has a modern service economy providing a growing financial, business, and health service base for the southern Mid-Atlantic region.

Greater Baltimore is home to six Fortune 1000 companies: Constellation Energy, Grace Chemicals (in Columbia), Black & Decker (in Towson), Legg Mason, T. Rowe Price, and McCormick & Company (in Hunt Valley). Other companies that call Baltimore home include, AAI Corporation (in Hunt Valley), Brown Advisory, Alex. Brown & Sons, a subsidiary of Deutsche Bank (of Baltimore origin, and at the time of its acquisition, the oldest continuously-running investment bank in the United States), FTI Consulting, Vertis, Thomson Prometric, Performax, Sylvan Learning/Laureate Education, Under Armour, DAP, 180°, DeBaufre Bakeries, Wm. T. Burnett & Co, Old Mutual Financial Network, Advertising.com, and Bravo Health.

The city is also home to the Johns Hopkins Hospital, which will serve as the center of a new biotechnology park, one of two such projects currently under construction in the city.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 13,503 |

|

|

| 1800 | 26,514 | 96.4% | |

| 1810 | 46,555 | 75.6% | |

| 1820 | 62,738 | 34.8% | |

| 1830 | 80,620 | 28.5% | |

| 1840 | 102,313 | 26.9% | |

| 1850 | 169,054 | 65.2% | |

| 1860 | 212,418 | 25.7% | |

| 1870 | 267,354 | 25.9% | |

| 1880 | 332,313 | 24.3% | |

| 1890 | 434,439 | 30.7% | |

| 1900 | 508,957 | 17.2% | |

| 1910 | 558,485 | 9.7% | |

| 1920 | 733,826 | 31.4% | |

| 1930 | 804,874 | 9.7% | |

| 1940 | 859,100 | 6.7% | |

| 1950 | 949,708 | 10.5% | |

| 1960 | 939,024 | −1.1% | |

| 1970 | 905,759 | −3.5% | |

| 1980 | 786,775 | −13.1% | |

| 1990 | 736,014 | −6.5% | |

| 2000 | 651,154 | −11.5% | |

| Est. 2009 | 637,418 | −2.1% | |

| City of Baltimore assumed its current borders in 1851, when it became independent of Baltimore County, Maryland. | |||

After New York City, Baltimore was the second city in the United States to reach a population of 100,000 (followed by New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Boston).[57] In the 1830, 1840, and 1850 censuses of the United States of America, Baltimore was the second-largest city in population, surpassed by Philadelphia in 1860. It was among the top 10 cities in population in the United States in every census up to the 1980 census, and after World War II had a population of nearly a million. The city and metropolitan area currently rank in the top 20 in terms of population. In the 1990s, the US Census reported that Baltimore ranked as one of the largest population losers alongside Detroit and Washington D.C., losing over 84,000 residents between 1990 and 2000.[58]

According to the 2006-2008 American Community Survey, the racial composition of Baltimore was as follows:

- White: 31.9% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 30.6%)

- Black or African American: 63.4%

- Native American: 0.2%

- Asian: 1.9%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: <0.1%

- Some other race: 0.9%

- Two or more races: 1.6%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 2.6%

Source:[59]

The population density was 8,058.4 people per square mile (3,111.5/km²). There were 300,477 housing units at an average density of 3,718.6/sq mi (1,435.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 64.85% African American, 31.28% white, 0.32% native American, 1.53% Asian, 0.03% Pacific islander, 0.67% from other races, and 1.47% from two or more races. 1.70% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. This census, however, does not accurately represent the city's Latino population, which, over the past few years, has been steadily increasing. This growth is mainly seen in the southeastern neighborhoods around Upper Fells Point, Patterson Park, and Highlandtown, and in the city's Northwestern neighborhoods such as Fallstaff, as well as various neighborhoods of Northeastern Baltimore.[60] 6.2% of the population were of German ancestry according to Census 2000.

There were 257,996 households, out of which 25.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 26.7% were married couples living together, 25.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.0% were non-families. 34.9% of all households are made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42, and the average family size was 3.16.

In the city, the population age spreads were 24.8% for persons under the age of 18, 10.9% for ages 18 to 24, 29.9% for ages 25 to 44, 21.2% for ages 45 to 64, and 13.2% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 87.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,078, and the median income for a family was $35,438. Males had a median income of $31,767 versus $26,832 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,978. About 18.8% of families and 22.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.6% of those under age 18 and 18.0% of those age 65 or over.

Crime

2009 saw 238 homicides in the city,[61] slightly higher than the 2008 total of 234,[62] which was the third-highest homicide rate per capita of all U.S. cities of 250,000 or more population.[63] Though this is significantly lower than the record-high 379 homicides in 1993, the homicide rate in Baltimore is nearly seven times the national rate, six times the rate of New York City, and three times the rate of Los Angeles.

Although other categories of crime in Baltimore have been declining, overall crime rates in Baltimore are still high compared to the national average. The rate of forcible rapes has fallen below the national average in recent years; however, Baltimore still has much higher-than-average rates of aggravated assault, burglary, robbery, and theft.[64]

City officials have come under scrutiny from Maryland legislators regarding the veracity of crime statistics reported by the Baltimore Police Department.[65] In 2003, the FBI identified irregularities in the number of rapes reported, which was confirmed by then-Mayor Martin O'Malley. The number of homicides in 2005 appeared to exhibit discrepancies as well.[66] The former police commissioner stated upon interview that the administration suppressed corrections to its crime reports;[67] however, many of the charges made by the police commission now appear to be politically motivated.[68] Under the administration of Mayor Sheila Dixon, who resigned after her conviction for embezzlement in 2009 (and is to be tried for perjury in 2010), and a new police commissioner, crime rates have been reduced, including a 17% reduction in the number of homicides from 2007 (a total of 282) to 2008.[69]

Government

Baltimore is an independent city, and not part of any county. For most governmental purposes under Maryland law, Baltimore City is treated as a county-level entity. The United States Census Bureau uses counties as the basic unit for presentation of statistical information in the United States, and treats Baltimore as a county equivalent for those purposes.

Baltimore has been a Democratic stronghold for over 150 years, with Democrats dominating every level of government.

Mayor

- For a full list of mayors who served the city, see List of Baltimore Mayors.

On November 6, 2007, former Democratic Mayor Sheila Dixon was elected Mayor. Dixon, as former City Council President, had assumed the office of Mayor on January 17, 2007 when former Mayor Martin O'Malley took office as the Governor of Maryland.

On December 1, 2009 Mayor Dixon took an Alford Plea on one count of fraudulent misappropriation by a fiduciary (embezzlement), a misdemeanor conviction.[70] On January 6, 2010 Mayor Dixon submitted her resignation, to be effective February 4, 2010. Former City Council President Stephanie Rawlings-Blake assumed the position as Mayor of Baltimore.[71]

Baltimore City Council

Grassroots pressure for reform, voiced as Question P, restructured the city council in November 2002, against the will of the mayor, the council president, and the majority of the council. A coalition of union and community groups, organized by ACORN, backed the effort.

The Baltimore City Council is now made up of 14 single member districts and one elected at-large council president. Bernard C. "Jack" Young is the council president and Robert W. Curran the Vice President. Stephanie Rawlings Blake serves as Mayor of Baltimore City as former Mayor Sheila Dixon resigned in early 2010.

State government

- See also: Baltimore City Delegation

Prior to 1969, some considered Baltimore and its suburbs to be particularly underrepresented in the Maryland General Assembly, while rural areas were heavily overrepresented. Since Baker v. Carr in 1962, Baltimore and its suburbs account for a substantial majority of seats in the state legislature; this has caused some to argue that rural areas are now underrepresented. Baltimore's steady loss of population, however, has resulted in a loss of seats in the Maryland General Assembly. Since 1980, Baltimore has lost four senators from the 47-member Maryland State Senate and twelve delegates from the 141-member Maryland House of Delegates.

State agencies

Several state agencies are headquartered in Baltimore. Executive departments include the Department of Aging,[72] the Department of Business and Economic Development,[73] the Department of Disabilities,[74] the State Department of Education,[75] the Department of the Environment,[76] the Department of General Services,[77] the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene,[78] the Department of Human Resources,[79] the Department of Juvenile Services,[80] the Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation,[81] and the Department of Planning.[82]

In addition the Department of Budget and Management,[83] the Department of Housing and Community Development,[84] the Department of Information Technology,[85] the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services,[86][87] and the Department of Veterans Affairs have offices in Baltimore.[88]

Independent agencies headquartered in Baltimore include the Maryland Commission on Human Relations,[89] the Maryland Health Care Commission,[90] the Maryland Lottery,[91] and the Maryland Tax Court.[92]

Federal government

Three of the state's eight congressional districts include portions of Baltimore: the 2nd, represented by Dutch Ruppersberger; the 3rd, represented by John Sarbanes; and the 7th, represented by Elijah Cummings. All three are Democrats; a Republican has not represented a significant portion of Baltimore in Congress since John Boynton Philip Clayton Hill represented the 3rd District in 1927, and has not represented any of Baltimore since the Eastern Shore-based 1st District lost its share of Baltimore after the 2000 census; it was represented by Republican Wayne Gilchrest at the time.

Both of Maryland's Senators, Ben Cardin and Barbara Mikulski, are from Baltimore, and both represented the 3rd District before being elected to the Senate. Mikulski represented the 3rd from 1977 to 1987, and was succeeded by Cardin, who held the seat until his election and inauguration to the Senate in 2007.[93]

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Baltimore. The Baltimore Main Post Office is located at 900 East Fayette Street in the Jonestown area.[94]

Law enforcement

- The Baltimore City Police Department is the primary law enforcement agency servicing the citizens of Baltimore: see main article here.

- The Baltimore City Public Schools Police is responsible for providing campus security for public schools of Baltimore.

- The Baltimore City Sheriff's Office (BSO) is the enforcement arm of the Baltimore court system. Deputy Sheriffs are sworn law enforcement officials with full arrest authority as granted by the constitution of Maryland, the MPCTC and the Sheriff of the City of Baltimore.[95]

- Organization-The current Sheriff is John W. Anderson. The BCSO is divided into several sections as follows:

- Field Enforcement Section

- District Court Section

- Child Support (Civil) Section

- Child Support (Warrant) Section

- Transportation Unit

- Warrant Unit

- Special Response Team

- K-9 Team

- Witness Protection Team

- Organization-The current Sheriff is John W. Anderson. The BCSO is divided into several sections as follows:

-

- Duties-The Sheriff is responsible for the following: security of city courthouses and property, service of court-ordered writs, protective and peace orders, warrants, tax levies, as well as prisoner transportation and traffic enforcement.

- The Maryland Transportation Authority Police is the primary law enforcement agency on the Fort McHenry Tunnel Thruway (I-95), the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel Thruway (I-895) and I-395 which are all under MdTA jurisdiction and have limited concurrent jurisdiction with the Baltimore Police under a memorandum of understanding.

Transportation

The Interstate Highways serving Baltimore are I-70, I-83 (the Jones Falls Expressway), I-95 (the John F. Kennedy Memorial Highway), I-395, I-695 (the Baltimore Beltway), I-795 (the Northwest Expressway), I-895 (the Harbor Tunnel Thruway), and I-97. Several of the city's Interstate Highways, e.g. I-95, I-83, and I-70 are not directly connected to each other, and in the case of I-70 end at a park and ride lot just inside the city limits, because of freeway revolts in the City of Baltimore. These revolts were led primarily by Barbara Mikulski, now a United States Senator, which resulted in the abandonment of the original plan. U.S. highways and state routes that run to and through downtown Baltimore include US 1, US 40 National Road, and the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. There are two tunnels traversing the Baltimore harbor within the city limits: the four-bore Fort McHenry Tunnel (served by I-95) and the two-bore Harbor Tunnel (served by I-895). The Baltimore Beltway crosses south of Baltimore harbor over the Francis Scott Key Bridge.

Baltimore is a top destination for Amtrak along the Northeast Corridor. Baltimore's Penn Station is one of the busiest in the country. In FY 2008, it ranked 8th in the United States with a total ridership of 1,020,304.[96] Just outside the city, Baltimore/Washington International (BWI) Thurgood Marshall Airport Rail Station is another popular stop. Amtrak's Acela Express, Palmetto, Carolinian, Silver Star, Silver Meteor, Vermonter, Crescent, and Northeast Regional trains are the scheduled passenger train services that stop in the city. Additionally, MARC commuter rail service connects the city's two main intercity rail stations, Camden Station and Penn Station, with Washington, D.C.'s Union Station as well as stops in between.

Public transit in Baltimore is provided by the Maryland Transit Administration. The city has a comprehensive bus network, a small light rail network connecting Hunt Valley in the north to BWI airport and Cromwell in the south, and a subway line between Owings Mills and Johns Hopkins Hospital.[97] A proposed bus rapid transit or rail line, known as the Red Line, which would link the Social Security Administration to Fells Point and perhaps the Canton and Dundalk communities, is under study as of 2007; a proposal to extend Baltimore's existing subway line to Morgan State University, known as the Green Line, is in the planning stage.[98]

Baltimore is served by Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, generally known as "BWI," which lies about 10 miles (16 km) to the south in neighboring Anne Arundel County, and by Martin State Airport, a general aviation facility, to the north in Baltimore County. BWI and Martin State airports are operated by the Maryland Aviation Administration, which is part of the Maryland Department of Transportation.[99] In terms of passenger traffic, BWI is the 24th busiest airport in the United States.[100] Downtown Baltimore is connected to BWI by two major highways (I-95 and the Baltimore-Washington Parkway via Interstate 195), the Baltimore Light Rail, and Amtrak and MARC commuter rail service between Baltimore's Penn Station and BWI Rail Station. Martin State Airport is linked to downtown Baltimore by two major highways, I-95 and U.S. Route 40, and MARC commuter rail service between Baltimore's Penn Station and its nearby Martin State Airport MARC Train stop.

Port of Baltimore

The port was founded in 1706, preceding the founding of Baltimore. The Maryland colonial legislature made the area near Locust Point as the port of entry for the tobacco trade with England. Fells Point, the deepest point in the natural harbor, soon became the colony's main ship building center, later on becoming leader in the construction of clipper ships.[101] After the founding of Baltimore, mills were built behind the wharves. The California Gold Rush led to many orders for fast vessels; many overland pioneers also relied upon canned goods from Baltimore. After the civil war, a coffee ship was designed here for trade with Brazil. At the end of the nineteenth century, European ship lines had terminals for immigrants. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad made the port a major transshipment point.

Currently the port has major roll-on roll-off facilities, as well as bulk facilities, especially steel handling.[102] Water taxis also operate in the Inner Harbor. Governor Ehrlich participated in naming the port after Helen Delich Bentley during the 300th anniversary of the port.[103]

In 2007, Duke Realty Corporation began a new development near the Port of Baltimore, named the Chesapeake Commerce Center. This new industrial park is located on the site of a former General Motors plant. The total project comprises 184 acres (0.74 km2) in eastern Baltimore City and the site will yield 2,800,000 square feet (260,000 m2) of warehouse/distribution and office space. Chesapeake Commerce Center has direct access to two major Interstate Highways (I-95 and I-895) and is located adjacent to two of the major Port of Baltimore Terminals. The Port of Baltimore is the furthest inland port in the U.S. with a 50-foot (15 m) dredge to accommodate the largest shipping vessels.

Education

Colleges and universities

Baltimore is the home of numerous places of higher learning, both public and private. Among them are:

Private

- Baltimore Hebrew University (BHU)

- Baltimore International College (BIC)

- College of Notre Dame of Maryland (CND or NDM)

- The Johns Hopkins University (JHU)

- Loyola University Maryland (LUM)

- Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA)

- Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University

- Sojourner-Douglass College

Public

- Baltimore City Community College (BCCC)

- Coppin State University

- Morgan State University

- University of Baltimore (UB)

- University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB, formerly UMAB)

Primary and secondary schools

The city's public schools are operated by the Baltimore City Public School System and include the historic Frederick Douglass High School, which is the second oldest African American high school in the United States,[104] Baltimore City College, the third oldest public high school in the country,[105] and Western High School, the oldest public all girls school in the nation.[106] Baltimore City College (also known as "City") and Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (also known as "Poly") share the nation's second-oldest high school football rivalry.[107]

Private schools

These private schools are within the city:

- Archbishop Curley High School

- Arlington Baptist High School

- Baltimore Junior Academy

- The Bryn Mawr School

- Boys' Latin School of Maryland

- Calvert School

- Cardinal Gibbons School

- School of the Cathedral of Mary our Queen

- Friends School of Baltimore

- Gilman School

- The GreenMount School

- Institute of Notre Dame

- Mount Saint Joseph College

- Roland Park Country School

- The Catholic High School of Baltimore

- Waldorf School of Baltimore

- Lab School of Baltimore

Parochial schools

- Archbishop Curley High School

- Bais Yaakov of Baltimore

- Cardinal Gibbons School

- The Catholic High School of Baltimore

- St. Frances Academy (Baltimore, Maryland)

- Institute of Notre Dame

- Mercy High School

- Mount Saint Joseph College

- Seton Keough High School

- Yeshivat Rambam

Media

Baltimore's main newspaper is The Baltimore Sun. It was sold by its Baltimore owners in 1986 to the Times Mirror Company,[108] which was bought by the Tribune Company in 2000.[109] Baltimore is the 26th-largest television market and 21st-largest radio market in the country.

Like many cities well into the 20th Century, Baltimore was a two-newspaper town until the Baltimore News-American ceased publication in 1986.[110]

In 2006, The Baltimore Examiner was launched to compete with The Sun. It was part of a national chain that includes The San Francisco Examiner and The Washington Examiner. In contrast to the paid subscription Sun, The Examiner was a free newspaper funded solely by advertisements. Unable to turn a profit and facing a deep recession, The Baltimore Examiner ceased publication on February 15, 2009.

Sports teams

Baltimore has a long and storied sporting history encompassing many teams from many different eras. The Baltimore Orioles have represented Major League Baseball locally since 1954 when the St. Louis Browns moved to the city of Baltimore. The Orioles advanced to the World Series in (1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979 & 1983), winning it (1966, 1970 & 1983), while making the playoffs all but one year from 1969 through 1974. In 1995, local player (and later Hall of Famer) Cal Ripken, Jr. broke Lou Gehrig's "unbreakable" streak of 2,130 consecutive games played (for which he was named the Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated magazine). Six former Orioles players have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. From 1953 to 1984, the Baltimore Colts played in the city under NFL Hall of Fame greats: Johnny Unitas, Art Donovan, Lenny Moore and many more. The Colts advanced to the NFL Championship twice (1958 & 1959) and Super Bowl twice (1969 & 1971), winning all except Super Bowl III in 1969.

The Baltimore Stallions were an expansion professional football team that joined the Canadian Football League in 1994. The Stallions remained in Baltimore for two seasons before relocating to Montreal after the 1995 season to become the Montreal Alouettes. The Stallions posted the best two season starts; advancing to the Grey Cup in each two seasons in Baltimore; of any Canadian Football League expansion team ever and the only U.S. based team in the CFL to win the Grey Cup, by upsetting the heavily favored Calgary Stampeders in their final season in Baltimore.

The NFL returned to Baltimore a year after the Stallions left. The Baltimore Ravens relocated from Cleveland in 1996 after Art Modell wanted a new stadium to replace the aging Cleveland Municipal Stadium where the Cleveland Browns played for 59 years. The team has had great success, including a Super Bowl Championship in (2000), two division championships (2003 & 2006), and two AFC Championship appearances in (2000 & 2009).

Other teams and events include:

The well known 2nd leg of the Triple Crown, Preakness Stakes at Pimlico Race Course every May in North Baltimore. Baltimore Blast of National Indoor Soccer League has had success winning championships in the last 8 years in (2003, 2004, 2006, 2008 & 2009) since est. 1992; Crystal Palace Baltimore an outdoor soccer franchise of USL Second Division since 2006; Baltimore Mariners of American Indoor Football Association since, 2008; completed an undefeated season in just there second year of existence, along with a championship in 2010; Baltimore Burn, National Women's Football Association since 2004; Baltimore Nighthawks, Independent Women's Football League since 2001; and the Charm City Roller Girls Women's Flat Track Derby Association since 2005. Area fans for example Wild Bill Hagy were and still are known for their passion and reverence for historical sports figures who played in the city or were born here.

Beginning in 2011, IZOD IndyCar Series will be making their debut in the city August 5–7 along the streets of Downtown Inner Harbor.

Sister cities

Baltimore has eleven sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International: [111]

See also

- Arabbers

- Baltimore Development Corporation

- Baltimore in fiction

- Baltimore Steam Packet Company

- Cemeteries in Baltimore

- Culture of Baltimore

- Dickeyville Historic District

- Eliza Ridgely

- Enoch Pratt Free Library

- List of parks in the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area

- National Bohemian

- Plug Uglies

- Royal Blue (train)

- Screen painting

- The Wire

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Donovan, Doug (2006-05-20). "Baltimore's New Bait: The City is About to Unveil a New Slogan, 'Get In On It,' Meant to Intrigue Visitors". The Baltimore Sun. http://www.redorbit.com/news/business/511672/baltimores_new_bait_the_city_is_about_to_unveil_a/index.html. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Smith, Van (2004-10-06). "Mob Rules". Baltimore City Paper. http://www.citypaper.com/arts/story.asp?id=9176. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ Kane, Gregory (June 15, 2009). "Dispatch from Bodymore, Murderland". Washington Examiner. http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/columns/gregory-kane/Dispatch-from-Bodymore-Murderland-48061142.html.

- ↑ "Why is Baltimore known as The City of Firsts?". City of Baltimore, Maryland. http://www.baltimorecity.gov/answers/index.php?action=artikel&cat=2&id=3&artlang=en. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ "Best Monument". 2005 Baltimore Living Winners. Baltimore City Paper. 2005-09-21. http://www.citypaper.com/bob/story.asp?id=10574. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ↑ "Ravenstown". Baltimore Ravens. http://preview.baltimoreravens.com/Ravenstown/Ravenstown.aspx. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ "More Literate than Akron". Baltimore City Paper. 2004-08-18. http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=8702. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ↑ "USGS detail on Baltimore". http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/f?p=gnispq:3:::NO::P3_FID:0597040. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009". US Census Bureau. 2003-10-20. http://www.census.gov/popest/metro/tables/2009/CBSA-EST2009-01.csv. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Baltimore city, Maryland". Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties of Maryland: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. US Census Bureau. 2010-03-31. http://www.census.gov/popest/counties/tables/CO-EST2009-03-24.csv. Retrieved 2003-10-20.

- ↑ "no title". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. http://www.dnr.state.md.us/fisheries/regulations/tidal_nontidal/central/patapsco1a.jpg. Retrieved 2009-02-09. Map shows the demarcation point between tidal and non-tidal portions of the Patapsco River.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009" (CSV). 2009 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March, 2010. http://www.census.gov/popest/metro/tables/2009/CBSA-EST2009-02.csv. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ↑ As a goodwill gesture, and based on this historic link, a statue of Lady Baltimore was sent back to Ireland in 1974 and erected there some years later. See Jensen, Brennen (2000-06-28). "Ms. Mobtown". Baltimore City Paper. http://www.citypaper.com/printStory.asp?id=2478. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ "Placenames". n-ireland.co.uk. http://www.n-ireland.co.uk/genealogy/placenames/placenamesb2.htm. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland". http://www.logainm.ie/?text=baltimore&uiLang=en&placeID=13321. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- ↑ Krugler, John D (2004). English and Catholic: the Lords Baltimore in the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0801879639. http://books.google.com/books?id=Lo5Bbf1AqYAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ "Baltimore, Maryland—Government". Maryland Manual On-Line: A Guide to Maryland Government. Maryland State Archives. 2008-10-23. http://www.msa.md.gov/msa/mdmanual/36loc/bcity/html/bcity.html. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ "The Great Strike". Catskill Archive. Timothy J. Mallery. http://www.catskillarchive.com/rrextra/sk7711.Html. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "Baltimore, October 17". Salem Gazette (Salem, Massachusetts): p. 2. 1827-10-23. http://docs.newsbank.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:EANX&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=10C5DE501F137990&svc_dat=HistArchive:ahnpdoc&req_dat=0F418C809CE5EA70. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ "The Baltimore Bank Riot". University of Illinois Press. http://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/34gcw3dk9780252034800.html. Retrieved 5 Jan 2010.

- ↑ Scharf, J. Thomas (1967). History of Maryland From the Earliest Period to the Present Day. 3 (2nd ed.). Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press. pp. 733–42.

- ↑ Duffy, James (December 2007). "Baltimore seals its borders". Baltimore Magazine: pp. 124–27.

- ↑ "Alabaster cities: urban U.S. since 1950". John R. Short (2006). Syracuse University Press. p.142. ISBN 0815631057

- ↑ "Baltimore Riots of 1968: A Timeline". University of Baltimore. http://www.ubalt.edu/template.cfm?page=1639. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "Who We Are". Maryland Stadium Authority. http://www.mdstad.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=12&Itemid=26. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Fritze, John (2007-01-19). "Dixon Takes Oath". The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2008-04-15. http://www.nr.nps.gov/.

- ↑ "Highest and Lowest Elevations in Maryland's Counties". Maryland Geological Survey. http://www.mgs.md.gov/esic/fs/fs1.html. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Average Monthly High and Low Temperatures for Baltimore, MD (21211)". The Weather Channel. http://www.weather.com/outlook/travel/businesstraveler/wxclimatology/monthly/graph/USMD0018. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ↑ NOAA, "Average Snowfall in Inches". http://lwf.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/snowfall.html.

- ↑ NOAA, "Maryland Average Annual Snowfall Map". http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/lwx/Historic_Events/md-snow-avg.gif.

- ↑ "US National Normal First Freeze". The Weather Channel. http://www.weather.com/maps/activity/garden/usnationalnormalfirstfreeze_large.html?clip=undefined®ion=undefined&collection=localwxforecast&presname=undefined. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Baltimore - Inner Harbor, Maryland, United States". Weatherbase. http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=074081&refer=. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ "Climatography of the United States No. 20 (1971–2000)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/climatenormals/clim20/md/180465.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ "Climatological Normals of Baltimore". Hong Kong Observatory. http://www.weather.gov.hk/wxinfo/climat/world/eng/n_america/us/Baltimore_e.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ Evitts, Elizabeth (April 2003). "Window to the Future" (PDF). Baltimore Magazine. http://www.browndowntown.org/files/april_balt_magazine.pdf. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Bishop, Tricia (April 7, 2003). "Illuminated by a jewel". The Baltimore Sun. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/baltsun/access/321974201.html?dids=321974201:321974201&FMT=ABS&FMTS. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Legg Mason Building". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=leggmasonbuilding-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Bank of America Building". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=bankofamericabuilding-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "William Donald Schaefer Tower". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=williamdonaldschaefertower-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Commerce Place". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=commerceplace-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "100 East Pratt Street". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=100eastprattstreet-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Trade Center". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=worldtradecenter-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Tremont Plaza Hotel". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=tremontplazahotel-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Charles Towers South Apartments". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=charlestowerssouthapartments-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "Blaustein Building". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=blausteinbuilding-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "250 West Pratt Street". Emporis Corporation. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=250westprattstreet-baltimore-md-usa. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ Mirabella, Lorraine. "Downtown jobs, housing boom". The Baltimore Sun. http://web.archive.org/web/20080127050520/http://www.ubalt.edu/jfi/jfi/Media/Balto_Sun/sun013007.htm. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- ↑ Fenton, Justin (May 31, 2009). "Assaults on rise in downtown, Inner Harbor". The Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/local/baltimore_city/bal-md.ci.attacks31may31,0,810921.story?page=1. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ Hermann, Peter (May 31, 2009). "Downtown gets riskier after dark". The Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/local/crime/bal-md.hermann31may31,0,4060018.story. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ "Profile of General Demographic Charaterics: Hillen" (PDF). Baltimore City Planning Department. http://censusprofile.bnia.org/Hillen%20Demographic%20Profile.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ↑ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: New Northwood" (PDF). Baltimore City Planning Department. http://censusprofile.bnia.org/New%20Northwood%20Demographic%20Profile.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ↑ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: Stonewood-Pentwood-Winston" (PDF). Baltimore City Planning Department. http://censusprofile.bnia.org/Stonewood-Pentwood-Winston%20Demographic%20Profile.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ↑ "Baltimore City Residents". City of Baltimore, Maryland. http://www.ci.baltimore.md.us/residents/. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ Smith, Tim (December 9, 2008). "Baltimore Opera seeks Chapter 11 protection". The Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/bal-te.to.opera09dec09,0,685458.story. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ↑ "Baltimore's African American Heritage and Attractions Guide:: Visual and Performing Arts". Visit Baltimore (affiliated with the Baltimore Convention & Tourism Board). http://www.baltimore.org/africanamerican/visual_performingarts.htm. Retrieved 5 Jan 2010.

- ↑ United States census data for 1830, 1840, and 1850

- ↑ "Top 50 Cities in the U.S. by Population and Rank (2005 Census)". Information Please (a division of Pearson Education, Inc.). http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0763098.html. Retrieved August 1, 2006.

- ↑ Census.gov

- ↑ "Baltimore city QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/24/24510.html. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ↑ "Baltimore Police: 2009 Ended with 238 Homicides". January 2010. http://baltimore.tewspaper.com/police-baltimore-ended-2009-238-homicides-four-08-trying-last-one. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ↑ "Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City, 2008". Uniform Crime Report, 2009. September 2009. http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2008/data/table_08_md.html. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ "Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City, 2006". Uniform Crime Report, 2006. September 2007. http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2006/data/table_08_md.html. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ "Baltimore Maryland Crime Statistics and Data Resources". http://baltimore.areaconnect.com/crime1.htm.

- ↑ "State Lawmaker Calls For Investigation Into Police". http://www.thewbalchannel.com/news/7057074/detail.html., WBAL-TV (February 14, 2006)

- ↑ "Homicide Rate, Police Procedures Questioned". http://www.thewbalchannel.com/news/7056945/detail.html., WBAL-TV (February 14, 2006)

- ↑ "Ex-Commish Raised Questions During Tenure". http://www.thewbalchannel.com/news/7341879/detail.html., WBAL-TV (February 22, 2006)

- ↑ John Wagner and Tim Craig, Wagner, John; Craig, Tim (February 14, 2006). "Duncan Rebukes O'Malley Over Crime". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/13/AR2006021301857.html. Retrieved April 26, 2010., Washington Post (February 14, 2006)

- ↑ "Homicides Down In Many Major Cities". http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/01/03/national/main4696974.shtml., CBS News (January 3, 2009)

- ↑ Bykowicz, Julie; Annie Linskey (December 1, 2009). "Dixon convicted of embezzlement". Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bal-dixon-trial1201,0,2096336.story.

- ↑ Nuckols, Ben (February 4, 2010). "Rawlings-Blake sworn in as mayor". Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bal-rawlings-blake-mayor0204,0,4678610.story.

- ↑ "MDOA Contact Information". Maryland Department of Aging. http://www.mdoa.state.md.us/contact.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Maryland Department of Business and Economic Development. http://www.choosemaryland.org/AboutDBED/Contact.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Maryland Department of Disabilities". Maryland Department of Disabilities. http://www.mdod.maryland.gov/. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "About MSDE". Maryland State Department of Education. http://www.marylandpublicschools.org/MSDE/aboutmsde/department_info.htm. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact the Office". Maryland Department of the Environment. http://www.mde.maryland.gov/ContactUs/index.asp. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "About DGS". Maryland Department of General Services. http://www.dgs.maryland.gov/overview/index.htm. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Directions—State Office Building in Baltimore". Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. http://www.dhmh.state.md.us/html/stoffbldg.htm. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Home Page". Maryland Department of Human Resources. http://www.dhr.maryland.gov/index.php. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Maryland Department of Juvenile Services. http://www.djs.state.md.us/contact_us.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation". Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation. http://www.dllr.state.md.us/. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Maryland Department of Planning. http://www.mdp.state.md.us/contacts.htm. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Maryland Department of Budget and Management. http://www.dbm.maryland.gov/portal/server.pt?open=514&objID=221&cached=true&mode=2. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Home page". Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development. http://www.dhcd.state.md.us/Website/footer_links/contact.aspx. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Maryland Department of Information Technology. http://doit.maryland.gov/about/Pages/ContactUs.aspx. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Information by Agency". Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. http://www.dpscs.state.md.us/contact_by_agency.shtml. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services". Maryland State Archives. http://www.msa.md.gov/msa/mdmanual/22dpscs/html/dpscs.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Information". Maryland Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www.mdva.state.md.us/contact.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Human Relations, Maryland Commission on (CHR)". Maryland Department of Budget and Management. http://www.dbm.state.md.us/phonebook/Level2Offices.asp?AID=CHR. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Information". Maryland Health Care Commission. http://mhcc.maryland.gov/mhccinfo/contacts.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Contact the Maryland Lottery". Maryland Office of the Governor. http://www.mdlottery.com/contactus.html. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Home page". Maryland Tax Court. http://www.txcrt.state.md.us/. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Official 2006 Gubernatorial General Election results for U.S. Senator". Maryland State Board of Elections.

- ↑ "Post Office Location—BALTIMORE". United States Postal Service / WhitePages Inc. http://usps.whitepages.com/service/post_office/33287?p=1&s=MD&service_name=post_office&z=bALTIMORE. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Baltimore CIty Sheriff's Office". City of Baltimore.

- ↑ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2008: State of Maryland". Amtrak. November 2008. http://www.amtrak.com/pdf/factsheets/MARYLAND08.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ "Maryland Transit Administration". Maryland Transit Administration. http://www.mtamaryland.com/. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Baltimore Region Rail System Plan". Maryland Transit Administration. http://www.baltimoreregiontransitplan.com/. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Maryland Aviation Administration". Maryland Aviation Administration. http://www.marylandaviation.com/. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Facts and Figures". Baltimore/Washington International Airport. http://www.bwiairport.com/about_bwi/facts_figures/. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ "History of the Port of Baltimore". Port of Baltimore Tricentennial Committee. http://www.portofbaltimore300.org/history.htm. Retrieved 5 Jan 2010.

- ↑ "The Port of Baltimore's Cargo, Maryland Port Administration". Maryland Port Authority. http://www.mpa.state.md.us/info/cargo.htm. Retrieved 5 Jan 2010.

- ↑ "Governor Ehrlich Names Port Of Baltimore After Helen Delich Bentley". Tesla Memorial Society of New York. http://www.teslasociety.com/bentley.htm. Retrieved 5 Jan 2010.

- ↑ "Film shows Baltimore school struggling despite No Child Left Behind law". Associated Press. 2008-06-21. http://www.globegazette.com/articles/2008/06/21/entertainment/tv/doc485dd0f84f4ed169476907.txt. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ Katz-Stone, Adam (2000-01-28). "School boundaries". Baltimore Business Journal. http://baltimore.bizjournals.com/baltimore/stories/2000/01/31/focus2.html. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ "WHS Flyer". Western High School. http://www.westernhighschool.org/academics/WHS_flyer.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ Patterson, Ted (2000). Football in Baltimore: History and Memorabilia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 7. ISBN 978-0801864247. http://books.google.com/books?id=cZeye8iTWyMC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ "The Times Mirror Company—Company History". fundinguniverse.com. Funding Universe. http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/The-Times-Mirror-Company-Company-History.html. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ↑ Smith, Terence (2000-03-21). "Tribune Buys Times Mirror". pbs.org (MacNeil/Lehrer Productions). http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/media/jan-june00/tribune_3-21.html. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ↑ "The Baltimore News American Photograph Collection". University of Maryland: Libraries. December 18, 2009. http://www.lib.umd.edu/RARE/MarylandCollection/NewsAmerican/Index.html. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "Baltimore City Mayor's Office of International and Immigrant Affairs—Sister Cities Program". http://www.baltimorecity.gov/government/intl/sistercities.php. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

External links

- City of Baltimore Website

- Visit Baltimore - Official Destination Marketing Organization

- Baltimore History Time Line

- Visit Baltimore

- Baltimore Grapevine The local interactive City Magazine

| Preceded by Philadelphia |

Capital of the United States of America 1776–1777 |

Succeeded by Philadelphia |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||